Harking back to our golden tri-force of process, product and culture I wanted to discuss today; process. And like a high school level research paper let’s start with a google definition:

“[Process] is a series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end.”

That’s pretty straight forward. You could compare it to a function in mathematics, given an input \(A\) how do you get to output \(B\). Typically that is more nuanced given multiple inputs to reach one or more decision-outputs. But process is more than just getting to the end, it gives you something much more powerful, the ability to track, monitor and enhance how you think about decisions.

Business that produce things have it made in terms of process. If you produce \(X\) widgets in \(Y\) time at a cost of \(Z\), you can measure and manipulate any of those attributes to make the process cheaper, faster or larger. Because the manufacture controls 99% of the process not only can you effect each action, but measure the interdependencies of actions. Because these are tangible items we tend to think this type of decision-making is limited to manufacturing or the production of ‘things’. Bullocks!

I hear this all the time in Local Government and Public Sector. “We’re different, things are straight forward, nothing is black and white, there are political considerations.” I get all of that, but how do you make decisions currently? Back of the pack calculations? Excel spreadsheets that only you can use? Hand written notes in a folder? And how do you learn from decisions once the ‘real’ answer is known? Your way might be better to you because it’s yours, but we are talking about transparency and inclusion in decision-making. There needs to be a better way and there is!

Introducing the Intelligence Cycle which has been purposefully designed, thoroughly tested and historically trusted process for making decisions!

This method provides the bones of a process that you need to fill in along the way, it is great for all those decisions that are nuanced and not well defined as it is flexible enough to accommodate multiple inputs and outputs in an iterative fashion. It has four distinct parts which we will discuss.

Requirements

First thing is to specify what you are trying to do. This is usually a board question with actionable elements. This is by far the most important stage. If you start in the wrong direction, it is hard to get back on course later or even find where the problems began. Remember, you put garbage into your process you’ll get garbage out.

Here are some intelligence questions we might ask;

“Given current production levels what will our profit look like in 6 months?”

“How does demographic make-up residents effect our service use?”

“What citizens represent the most ‘vulnerable’ in our borough?”

Note the above examples have three elements, a subject, a measure and a constraint. Or, an input, and output and a constraint.

| Subject | Measure | Constraint |

|---|---|---|

| Production | Profit | 6 months (Time) |

| Residents | Demographics | Services Provided (Categorical) |

| Citizens | “Vulnerability” | Borough (geographic) |

Subjects are important because they describe the who and what make up the decision space. People behave differently from machines and are different from passive service use, so those nuances will affect the analysis.

Measures help specify what you are observing. Profit means we might ignore expenses, human and capital costs, We will need to define “Vulnerability” as an measure but it might include the number of homeless, adults and children with mental health issues, etc.

Constraints keep your analysis from going down rabbit holes and bookending the limits of what you can explain (see my post call Leverage for when people over interpret analysis). Time, categories and geographic boundaries are some of the constrains you might have but they will keep you and your decision-maker focused.

“But Jake, the world is a complex interconnected place. You cannot dumb down these issues to processes and analytical units. Why do we even have science? I am going to trust my gut and weak human brain to keep all the complexity in my head and make a purely objective decision!”

Bullocks!

Analysis isn’t perfect, or indeed can never explain causation with 100% assurance, but it’s a damn sight more objective, rigours and true than what our cognitive machinery puts out. Remember, only half of people can see the gorilla.

And you don’t need to single source requirements, you might ask multiple questions that when presented Altogether give you the insight to make a decision. That is the part humans are good at, but you need data to achieve it. It is not unheard of to have several intelligence requirements and five to ten questions for each.

Collection

Now that we have our requirements we need data and information. I cannot really speak to this part in universal terms, the requirements will drive your collection which will vary from analysis to analysis. But in a data rich world there are measures and proxy measures out there to assist with anything now a days. Or if you are a large company, you likely have lots of data you didn’t even know you had. This might take the form of public consultations, formal questionnaires, open-source data sets, a mishmash of several organisations data, etc.

Just remember the Doug Hubbard adage. “You have more data than you need, and you need less data than you think.”

Analysis

This is the part of the cycle that often goes off the rails. As simple questions rarely lead to simple answers. But analysis is an academic process which will have its own methodology, internal logical and measurement. This is where we might write a summary of finding, run a regression analysis and build a machine learning algorithm.

The analysis must suit three conditions. Without all three of these elements you output will mean nothing.

It must represent the data

It must answer the question (directly or indirectly)

and it must provide a measure of confidence in its accuracy, ability to explain the topic or error.

Dissemination

How do you report back to your decision-makers. That will depend largely on your audience. Some things to ask might be;

- How much detail do they want?

- Perhaps they only need a two page briefing rather than your epic 100 page tome of research

- Perhaps they only need a two page briefing rather than your epic 100 page tome of research

- Is the end goal to;

- Describe what is happening?

- Estimate what will happen?

- Explain how something works or may come about?

- Or interpret research to gain insight?

- What is the best medium for communication?

- If it is a crowd maybe a PowerPoint?

- If an intimate briefing a short paper and long chat to answer questions

- Always try to supplement any briefing with an face to face oral briefing so things never get mis-construed.

- Did you answer the original question(s)?

- Yes and I have the research to back it up

- No, it was the wrong question or there is too much uncertainty

- Maybe, in light of findings we change tactics

- Is there is a “So what?” to your analysis, are you providing something new

I haven’t gone thought things in excruciating detail, because this is intuitive right? Even if we are up against deadlines and we make sacrifices for time we still follow this process. The goal is to get from a question to an answer that either generates a new question, one that either clarifies, or increases in detail as our knowledge increases.

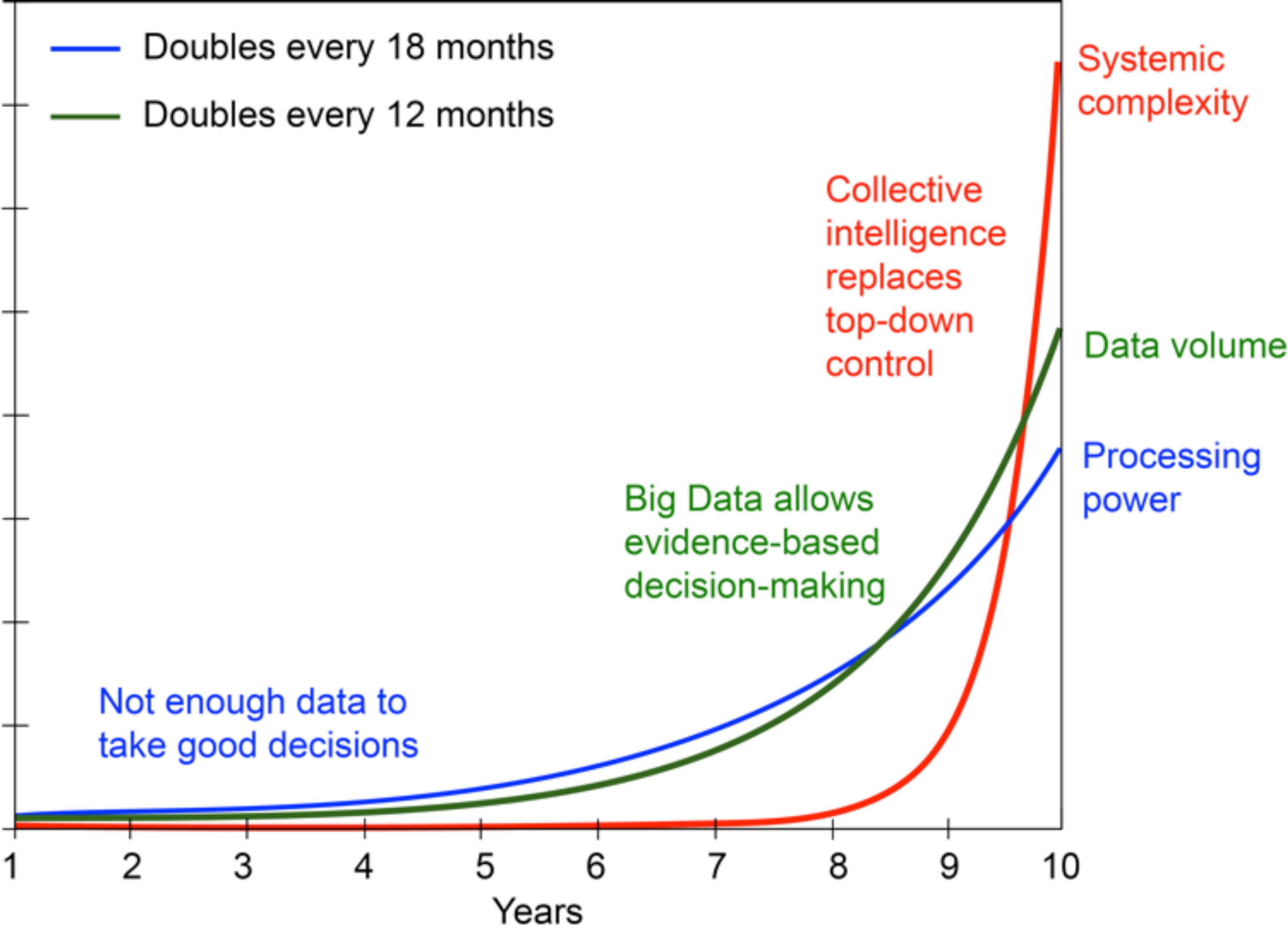

The added benefit now is the ability to interrogate each stage of the process for weakness. Often people are great at coming up with requirements and the results get less and less as the work progresses. Perhaps you find you do need more data, more in-depth analysis, a better way to communicate results. I quite like the diagram below from Dirk Helbing as it highlights the journey that intelligence-led decision making can take a business on. You start from knowing very little and making decisions on the fly to an ever increasing, robust system fed by power (ability), data volume, and system complexity.

I can go on and on with examples but they will never cover every iteration. The key is that the intelligence cycle provides rigor to an other wise amorphous process. The intelligence cycle adapts to the type of data, methods and audience you are reporting to, and having separate stages of the process allows you to see what is and is not working.This allows you to improve short medium and long term decision making. Without rigor in method we never truly create knowledge. We never know where we started, where we end or how we ever got here and that is a very lonely place to be.