TL;DR

Questions trigger visceral reactions in our mind that cause small gaps of cognitive vulnerability when our decision-capacity is at its weakest. This is what allows click-bait and other curiosities to get the better of us. We can train our brains to avoid such patterns like learning to look both ways when crossing the street as a child, or remembering to turn off the lights before leaving the house. Learning to recognize mental pitfalls will make us less susceptible to the traps used by advertisers.

TS;WM

Questions are powerful things. We ask questions everyday, consciously and subconsciously; “Should I cross the street?”, “Did I turn off the lights?”,”What time is that appointment?” We repeat these things to ourselves not only to remember, but to train ourselves to recognize patterns. These are all simple things that as children we learn, committing them to memory and mnemonics to simply go on autopilot. Other questions get more serious and have unknown outcomes and cause our brains a great deal of work; “What flavour milk-shake do you want?”, “Which shirt do you like more?” These questions require a different algorithm that literally generates more heat and fatigue. Then there are the big questions! “Will you marry me?”,”Why do you wanna work for X company?”, “Do you want to receive treatment or not?” There is a great book I can recommend if you want to learn more called “Thinking Fast and Slow by” by Daniel Kahneman. I will not presume to cover this topic in the detail Kahneman does, but I’ll have a go. After all, this is what this blog is about!

All of these questions grab our brains and give them a shake, obviously some more than others, but they all capture our imagination and cause a visceral reaction that quickly gives way to a thorough evaluation of pros and cons, like and dislikes, knowns and unknowns. Like when someone says “Choose, don’t think.” I was never very good at that. But implicitly can be one of the purest forms of cognitive measurement as we are acting on instinct. That is where the idea of “click-bait” was born, in the short recesses of mental fatigue, or rather, over activity, where we are most vulnerable and suspliable. You know the articles; “Doctors can’t explain this one thing…”, “Are people who eat fat really less healthy?” They prey on those cleavages between our rational thought and before you know it the page is loaded and we are reading about some Love Island star, a show I don’t watch, and for what? Curiosity. Thats why. Neil Patel has a good blog post about this in which he explores how click-bait is just a tool for Search Engine Optimisation and driving site traffic. It is not designed to inform or even be interesting, it is just a churn system for websites to sell advertising. I feel dirty thinking about it.

We humans are simple creatures at the end of the day. Sure, we try to act smart. We look the part. However even the smallest inkling of danger or terror and we squeal like school kids. At the end of the day, we just want to be loved, eat, sleep, not die, and get a little lucky procreate to further the human race. Clickbait knows this. Acknowledges it. Understands it intimately. It tickles our curiosity while dumbing down concepts into a common language we can all understand. Like: fear, greed, jealousy, envy, lust, and more.

Neil, mate, that is some bleak stuff… god I hate that you’re right. Closure is a natural human cognition. It was most useful when we were not at the top of the food chain, it allowed us to take a little information, in a fraction of time and allow us to make life and death decisions. Now it is used to promote pseudoscience adverts that props us failing newspapers. Progress!

But I am drifting now, so let’s draw back. Questions draw out that primal, visceral reaction from us. Imagine you see a car coming toward you. Physically your muscles tense, your hair stands on end and your adrenaline starts pumping. In you mind, your synapses are firing on all cylinders brining all knowledge it can to bear on the situation; estimating the speed of the car, its distance, which way you need to move and how fast, how big the car is, a damage assessment if it does hit you, even trivial things like make and model might cross your mind in that split second. But the same works for questions; “Will COVID-19 change the way we work?” You brain will starting pulling in information a covid; its a virus, it’s dangerous, it has been around for months, its not going away, it has killed many people, it is the reason I wear a mask, many people were laid off and others work from home, so the answer is yes! And the article is already loaded, the advertiser has made its impression and you are stuck reading an opinion piece on something you already knew. Mental fuel expended for no reason. Well, capitalistism is the reason. There is a phenomena at hand called the Betteridge Law, coined by Ian Betteridge, a british journalist in 2009. The law states;

“Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no”

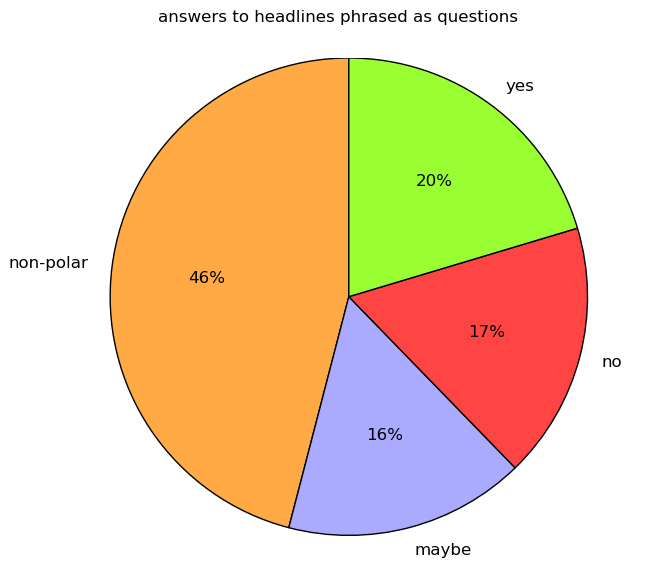

Imagine if that is true, then the click-bait industry should die, shouldn’t it? We all just commit to remembering the rule, like we did about crossing roads, and turning off lights and voila! Well, like most things on the internet, it is not black and white. Mats Linander in 2015 wrote an article called is betteridge’s law of headlines correct?, a very tongue in cheek title, yes, indicating the law is NOT true, but the findings were interesting. Linander looked at 26,000 headlines and found 766 which had question marks at the end and sought to answer them. He split them into two categories; Polar, those that could be “yes”/ “no” answers, and non-polar, indicating that more nuance was needed to provide an answer.

Linander found 54% (414) of articles were polar yes/no questions. But that wasn’t enough, the question still is if 54% of preposition articles will have a “no” answer. Well, no, if fact, they won’t. Only 17% were no, 20% yes and 16% maybe. So there you go, a small one off test that provides some evidence that Betteridge’s law is hardly a universal constant.

Mats Linaders, 2015

Mats Linaders, 2015

So where does that leave us. We still have click-bait, our minds are still making bad decisions when they fall into the trap and I have no tool for evaluating headlines. Well what about the analysis of Steve Rayson in a Buzzsum article form 2017. Rayson looked at 100 million headlines for patterns of engagement. What he found was facining.

Steve Rayson, 2017

I don’t know about you, but those are some click baity titles if I have ever seen some. Granted, his analysis is based on Facebook engagement, and you could draw some broad assumptions about readership, but the platform will be different from other news sites and we have no data on ‘click-through’ where you jump from sight to site. The call to action dear reader is that your mentaly machinery is faulty and easy exploited like an old piece of software. The onus is on us as consumers to critically evaluate the headlines that you see, and while this is a scatter gun tour, I recommend the articles linked within for some interesting reading. I am reminded of the words of Ricahrd Dawkin’s “Science is cumulative, and we live later.” We know click-bait is bad and wrong and while our ancestors might have not known about the cognitive impacts of this phenomena we can and do know it all too well. And it’s not just the scummy exploitation of our cognition, but the dodgy business and industry is supported by mis-information, bad journalism and our need to indulge the voyeuristic misery of the latest celebrity who has fallen from grace. Act better and demand better, it is not the media’s fault. WE made them this way and we need to unmake them.